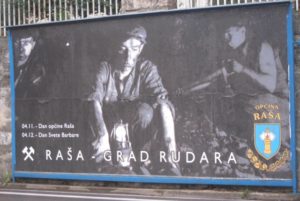

On the website https://soundcloud.com/markotadik/sets/13-pieces-for-prvomajska one can listen to the sound installation by artists Marko Tadić and Miro Manojlović “Concrète machines: 13 pieces for Prvomajska”. These sound pieces have been used at the exhibition in the framework of The Second Biennale of Industrial Art in Istria under the title “On the Shoulders of Fallen Giants.” The installation was placed in the cinema hall in Raša, a small mining town, known as the youngest town in Istria: it was built in 1936 and 1937 to be home of miners and their families. The mines were closed only 30 years later, and the town is today just a monument to mining life and labor. The cinema hall also lost its function – its interior is emptied of seats and void of function. It is just one among many empty, ruining buildings in this town, built by Italians during their administration in Istria. The town that was carefully conceptualized to cater the needs of its inhabitants, for a long time already stands still, bond with the past, as a monument to a bygone era, and as a ruin of the imagination of the future that industrialization used to embody.

Marko Tadić thus explained the installation in the Biennale’s catalogue: “I went to Raša as an observer, looking for visual feedback on my new work. When I entered the Prvomajska (1st May) factory in Krapan, I was surprised by the silence of the abandoned factory hall. The acoustics of the space magnified nearby sounds, and everything that echoed inside made the factory sound like a concert hall. At that moment, I decided that on this occasion, my work would be in the medium of sound. Since I am not a musician, nor a composer, I invited Miro Manojlović to collaborate with me. I gave Miro the drawings based on the space and the machinery at Prvomajska, so that he could interpret them as partitions and play them as “compositions” on the machines. These metal giants, that had once produced completely different sounds, became acoustic instruments with a broad tonal range over the course of our performance. For a few hours, the sound recordings we produced enlivened the space of the factory that had once employed more than a thousand people. The sounds and the noise therein returned to this impressive industrial space, which had once fed, schooled and brought together a community of workers and their families.”

Although “13 pieces for Prvomajska” kept living their virtual, “de-territorialized life” on the SoundCloud platform, it is the abandoned space in the center of a deindustrialized mining town where we could observe their full capacity to disrupt the silence and bring back the noise of machines and production. Emptiness and silence became dominant ways to experience and describe the process of deindustrialization, but also, as Dace Dzenoska argues, “a powerful lens for analyzing novel relations between capital, the state, people, and place.”

The artistic take on industrial noise transforms noise into sound, but among silent and empty ruins of industry and the bygone world the industrial labor has created, the sound acquires additional agency: the sound becomes a voice, understood as “a phenomenon that links material practices with subjectivity, and embodied sound with collectively recognized meanings” and a “critical site where the realms of the cultural and sociopolitical link to the level of the individual”, as Amanda Weidman argued. Such voice is capable of recalling lost social relations, values and alternatives to what became the present, characterized by silence, stillness, emptiness and dissolution.

For the visitors of the Raša installation, the artistically fashioned industrial sounds were readable, and also productive of affect, exactly because on this capacity. Listeners’ affective response was largely conditioned by situatedness of this performance into concrete material and historical context. This response is not triggered by a mimetic recollection of the sounds that used to make a soundscape in industrial towns and cities: for Tadić and Manojlović, machines could become instruments only because of the fact that “they used to produce very different sounds”; it is not their acoustic capacity that makes them instruments, not the sound they can produce (now), but the sound that they used to produce in the past and the historically grounded knowledge about the past existence of that sound in industrial towns, and the awareness of what it meant for the social worlds created around noisy industrial complexes.

Opera industriale, a performance held in the Rijeka harbor at the opening ceremony of the European Capital of Culture in February 2020 is another example of mobilization of sonic affect that stems to a historically situated knowledge: directed by Dalibor Matanić, this more than 50 minutes long show, abundant with industrial sounds, and scenography enacting industrial production process generated strong affective response. Tightly linked to a discrete industrial history of Rijeka, but also to its loss, the arrhythmic, distortive sounds coming from the stage could produce intense emotions not so much for their direct, artistic/musical value, but because they evoked what used to exist and what has been lost in the transition from the 20th century modernity based on industrialization and socialism, to the neoliberal present-day reality characterized by raising inequalities and often uncanny divisions of the urban space. Referring to this reality, Croatian columnist Jurica Pavičić noted that “next to the main stage where the industrial opera has been performed, there is a wharf that was built for an economic activity.” Today, this wharf host rich people’s yachts in the winter period, and next to it is Molo longo, a popular promenade that was subject of a controversy in time of the opening of European Capital of Culture, as the city authorities placed the fence there, so citizens walking by would not damage expensive yachts and ships.

(picture taken from https://rijeka2020.eu/en/press/opera-industriale-transforms-rijeka-port-into-an-amazing-stage-leading-rijeka-into-a-year-of-the-european-capital-of-culture/)

Many of those who attended the opening performance on a rainy February evening, and those who watched its recording in the following days, felt that industrial sounds, songs and visual effects were capable of powerfully evoking the lost identity of the industrial city and its once vibrant port. Affective identification that this evocation made possible was not premised on forgetting the present-day reality in which there is no place for industry and visions of the future it entailed, and where tourism and renting valuable coastal and marine space to the rich became the only source of income. The loss of industry, sensually materialized in silence, emptiness and absence of workers – is constitutive to this affect. The very possibility to bring back the noise of machines and labor to former industrial spaces and thus evoke a different sociopolitical reality was actually enabled by the practices, which in a way confirm definiteness and irreversibility of that loss: to be brought back, the industrial past needs to become part of heritage, as in the case of the installation in the abandoned cinema hall in Raša, or European cultural narratives emphasizing the value of creative industries, in the case of Rijeka as European Capital of Culture 2020. While this fact tells a lot about the neoliberal condition that regulates the possibility of articulation of certain voices and positions, it should not obscure both theoretical and political importance of the historically grounded affect, bound to concrete spaces, which emerges from these articulations.

(picture taken from https://rijeka2020.eu/en/press/opera-industriale-transforms-rijeka-port-into-an-amazing-stage-leading-rijeka-into-a-year-of-the-european-capital-of-culture/)

Both voice and affect are concepts with a lot of currency in ongoing debates in the humanities that concern political subjectivity and possibilities for imagination of political and social alternatives to global neoliberalism. Researchers are prone to see potential of these concepts in their universality, pre-personality, and precultural significance. Within the framework of the affective turn, the understanding of affect turns “away from something labelled with many terms, such as language, reason, cognition, meaning, signification, discourse, positions, identities, structures, subjectivity or representation,” in order “to draw attention to immanence, to bodies, to their attunement to each other and to objects, which are considered to function prior to all of the above” (Jansen). As Ana Hofman points out, such orientation tells “much less about the very nature of affect, and much more about a desire to radically reshape our understanding of where and how we search for political potentialities.”

But is the affective response to sounds that recall industrial noise in places such as Rijeka or Raša void of political potentiality? It is firmly historically grounded and its social meaningfulness stems from concrete conditions of existence and discrete spatio-temporal context, in which is very difficult, if not impossible, to articulate an alternative to the prevailing neoliberal reality through available political discourses. Affect’s capacity to transform industrial noise to a voice of critique comes from this situatedness and concrete experiences of both the world based on modernist industrialization, and the loss of that world. Articulated amid industrial ruins, this voice makes them “unsettled and unsettling” (Blackmar), and prevents the pacification, aestheticization and fossilization of the memory of industrialization and its reduction to a linear historical narrative – all common results of processes of musealization and the making of industrial heritage (Barndt; Muehlebach; Petrović). It points not only to the shared, intimate knowledge of the past, but, even more importantly, to an affective orientation “toward a radically different future and a conceptual framework of modernity inherited from the past” (Bryant and Knight; Dzenoska).