Pavao Markovac was a musicologist, publicist, critic, political agitator, organizer, and a prominent member of the so-called Croatian left intelligentsia between the two World Wars. His extremely rich political and artistic work within the labor movement regularly, however, remained outside the narrow focus of scholarly debates. To illustrate, Nataša Leverić Špoljarić in the text “Pavao Markovac (1903–1941) – a musical enlightener between two world wars (on the 80th anniversary of his death)” (sic!) almost completely bypasses this part of his work, citing it only as a biographical episode, while other aspects of his work are elaborated in more detail. The reasons for omitting this key aspect still wait to be investigated, but it would not seem wrong to attribute them to historical revisionism, which casts a shadow on many fields and many depictions of left-wing artists and cultural workers of the interwar period. In different encyclopedic entries about Markovac there is only a remark that he wrote about music from a Marxist perspective, which does not show the width, complexity and intertwining of his journalistic, political and artistic work, based on the Marxist tradition. This text does not pretend to completely fill this gap, but to re-initiate the debate introduced by Markovac himself, which is, in short, on Marxist interpretations of music, its production, reception and, finally, it’s role in the society.

Historical context and biographical background

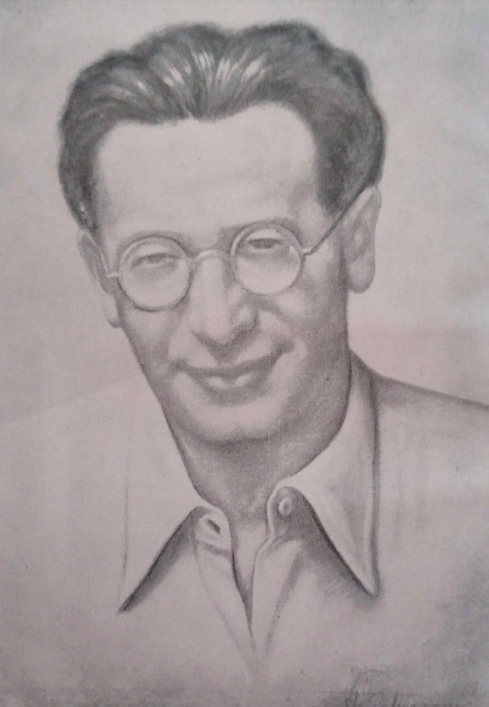

Pavao Markovac was born on April 5, 1903, in a Jewish bourgeois family as Pavle Ebenspanger. While in high school, he attended private piano lessons and the then Croatian Conservatory music school. Contrary to expectations, after graduating from high school he enrolled in the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Vienna, where he studied musicology with Guido Adler and Robert Lach, and obtained his PhD in 1926. It was his stay in Vienna in the 1920s that would be crucial to the development of his Marxist position. There, according to the testimony of his first wife, Valerija Singer, he showed great interest in social issues, as well as in the problems of contemporary art. Upon his return to Zagreb, he became an associate of the Zagreb Radio Station, and then of the Edison Bell Penkala records factory.

It was in this period that he began his extremely rich journalistic work, in which he slowly began to present, at the time radical, Marxist-based theses on art, with a particular focus on the field of musical art. In the period from 1927–1941 he has written over 600 articles for various newspapers, magazines and magazines. This multitude of texts, critically oriented towards the dominant and reactionary ideas of the bourgeois musical life in Zagreb brought him a certain isolation reinforced by the political repression of the Communist party members and sympathizers in 1930s Yugoslavia. After returning from his studies in Vienna, Markovac encountered very unfavorable socio-economic and political conditions. At the time, class differences were becoming more pronounced, the pressure on workers was growing, and the impending crisis of capitalism was being felt throughout the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. Possibilities for radical action have been limited since the 1920 document “Obznana” which banned the work of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, as well as all other professional, sports and cultural organizations within which the politicization of workers was conducted. The document also bans strikes as a basic political tool of the working class. The culmination of political repression came with the establishment of the January 6 dictatorship in 1929 – the banning of the work of political parties, unions, as well as political rallies and the introduction of strict censorship put additional pressure on any form of radical political action. Under these conditions, the Communists went underground and tried to offer organized resistance to the regime through a network of various party organizations.

One of the areas of fight took place “on the left literary, journalistic and cultural front” which Markovac was a part of. Although hundreds of communists were killed in regime purges in the first few years of the dictatorship, and a significant number ended up in prison, a critical group of young intellectuals emerged who managed to achieve significant success on this front. In the 1930s, the party accepted the concept of the People’s Front from the International Communist Movement, ending the isolation of the Communists and beginning work in alliance with other mass organizations that were not necessarily on the same political line as the Communist Party.

A particularly important political factor at the time was the United Workers’ Union (URSS), which, despite its reformist tendencies, had gradually been joined by communists since 1932. That year, Pavao Markovac joined the URSS, and became one of the main organizers in the field of amateur music activities. With his professional help, “numerous workers’ cultural and artistic societies, choir ensembles, instrumental ensembles and theater companies appeared within the trade union branches in Zagreb.” The organization of various amateur artistic activities does not only follow the idea of left-wing policies to change the political-economic system, but to change, or rather, to create a new mass working culture. Despite constant police surveillance and censorship, this type of cultural and artistic organization managed to resist the pressures of the regime, becoming an important place of agitation and mobilization of the working class.

Markovac’s role in the labor movement is multiple. As a music expert, he was a key person in the formation and ideological direction of many choral and instrumental ensembles. At the same time, he participated in many ways in the work of these ensembles (as a conductor, composer, and above all as a political worker). He also contributed to the intensive work on the cultural enlightenment of the working class through organizing and managing different amateur musical activities within the labor movement, and he was also a member of Agitprop of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Croatia. Because of his communist ideas and actions, he was eventually arrested on March 31, 1941 and detained in the Kerestinec camp. On the night of July 13–14, 1941, he took part in an attempt to escape with other interns from Kerestinec, after which forty-four of them were detained in the basement of a house on Franje Račkog Street. On July 17, 1941, he was shot in a forest in Dotrščina on charges of attempting to rebel against the Ustasha government.

Markovac, music, and historical materialism

Eighty years after the murder Markovac figures as a solitary figure in the national history of music. He remained among the few who approached music from a historical-materialist perspective, as I discuss in more detail below, by dissolving the idea of its relative autonomy and tried to build a new musical culture and change the production relations within the field of music with the idea of new socio-political conditions. Today, his writings could bring us an inspiring insight to what it means to produce and practice a radical approach to music in the time of crisis. His writings are primarily of a journalistic nature, but they also contain a very clear political dimension. Apart from being a valuable historiographical insight into the social relations in the field of music production of the time, these texts nevertheless are a radical intervention (unfortunately without further development) within the discipline of musicology, which places music production in the context of broader socio-economic relations.

Markovac’s entry position in the critique of the field of music is based on the key assumption of the Marxist tradition about the material conditions that shape human consciousness. At the very beginning of his text “Music and Society,” Markovac notes: “History proves that intellectual production is transformed with material production. With the living conditions of man and with his social existence, his notions, views, in short, his consciousness changes. Man’s social position determines his view of the world. Therefore, every artist, consciously or unconsciously, is an ideologue of a class.”

In this sense, music production is not exempt from the real social and material relations within which it is produced. The way music is produced, as well as its role in society, is changing along with political changes and the changes in the mode of production. For example, what we know today as Western European classical music is for the most part a reflection of the aspirations of the ruling class to maintain its position and as such takes different forms within different historical, social and productive constellations. With this approach to the field of music, Markovac introduced what will only later on be more precisely theoretically articulated as the critique of the autonomy of the general artistic and musical field from social and material production relations, especially since the emergence of bourgeois society and capitalist mode of production.

All art, that is, what in a bourgeois society is perceived as art, represents for him a field of ideology that conceals real social relations and consolidates the status quo. Therefore, artists, as Markovac points out, “consciously or unconsciously”, become the bearers of the ideology of the ruling class and reproduce these ideas in their works. From that follows that all stylistic and compositional-technical procedures, possibilities of performance and reception of an artwork are shaped by material conditions of production in the hands of the ruling class, and are at the same time its ideological tool in which the artist plays a mediating role without knowing that he “does not create his work on his own free will, nor under the conditions he has chosen, but under the conditions which already exist, which he has inherited.”

On the same track, Markovac historizes the very notion of the artist and the cult of genius as created in bourgeois society. At the level of musical style, geniuses are seen as special instances that, with the power of their talent, manage to create “eternal” works that play a key and defining role of a certain period. Markovac points out that, despite common assumptions, those who are perceived as geniuses, on a formal and technical level, neglect the works of other artists, and are credited for what is the result of collective artistic work in a historical moment.

This also neglects the material conditions of the very artistic labor in capitalism. About this Markovac writes: “While thinking of artistic creation in a trance and an artist living in some higher spheres, it was difficult to admit that the composer has always been dependent on his employers (church, aristocrats, state, bourgeois patrons, publishers or audience), that art was actually created for the one who paid.” While earlier composers were employed in a church or court (often nothing more than ordinary servants), with the establishment of a capitalist mode of production and the growing development of bourgeoisie at the turn of the 18th and 19th century, the notion of a free and independent composer appeared for the first time. The notion in which the composer no longer writes representative works according to the needs and aesthetic standards of his employer and is no longer formally employed. Although on the aesthetic level liberation from wage labor gives him more freedom for his own artistic expression (which will result in a high level of artistic individualism), “he nevertheless comes into a new dependence: on the performer, the audience and, later, the publisher. In terms of production conditions and the economic structure of bourgeois society, the work of art also becomes a commodity” – in short, it enters the free market.

Markovac also engaged with the key issue of art made in accordance with the new socio-political conditions to come: shall revolutionary movements adapt the “preexisting” cultural and artistic forms and legacies to the needs of the working class at a time of growing class conflict between the two world wars, or is it necessary to create a completely new art and culture that will be in line with the political program of the growing labor movement?

For Markovac, this problem comes into focus when he enters the labor movement and faces a lack of repertoire that would be suitable for cultural, artistic and political needs of the working class within the amateur cultural and artistic organizations. In these circumstances, he writes, “lacking better works, workers’ music societies resort to works that not only do not meet workers’ needs, have no musical value and spoil taste, as they are of no use to the worker – but these works, seemingly harmless, overwhelm him with reactionary (backward) thoughts and feelings.”

Markovac presented his ideas on workers’ culture and music in detail in the discussion Radnička muzika[Workers’ music], published in 1936, which was soon followed by the publication of Naša pjesmarica [Our Songbook], a collection of revolutionary songs in simple arrangements suitable for workers to sing, which was distributed in 10,000 copies. For Markovac, the problem of bourgeois music was not only at the level of aesthetics and ideological orientation, but also at the performance level. He writes: “evening events, which are attended in ceremonial attire, correspond to the way of life of a bourgeois society, and exclude workers from their visits.”

Namely, the main social forms of performing music within the bourgeoisie are public concerts, which, according to Markovac, “take music away from the public, they are an event outside everyday life, without connection with daily events”. They are developed in parallel with the seeming “liberation” of composers and musicians from wage labor, representing for the “free” composer or musician the main source of income on the market. Since the concerts are paid, access to them is possible with a paid ticket or subscription, which prevents workers from attending concerts. The proclaimed “democratization of music reception” thus remains limited to a narrow circle of the bourgeois class.

Markovac saw yet another problem in the apparent autonomy of classical music: “bourgeois artists declare that art is above reality, that it is not concerned with it and that it may never enter the sublime temple of pure art.” According to Markovac, the bourgeois art of that time put an emphasis only on form while ignoring content: “there is no trace in it of an increasingly difficult social situation, of an increasingly sharp conflict between opposing social forces and greater and more terrible misery” [of the people].

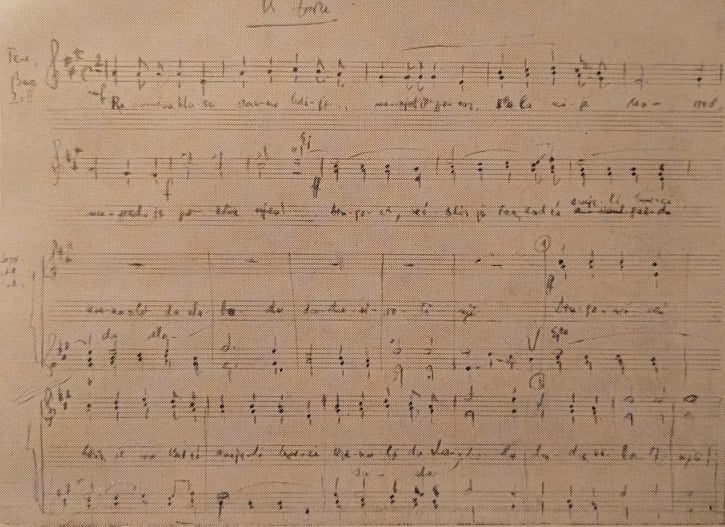

Instead, Markovac argued for an equal importance of what is expressed and how it is expressed in music. In other words, working-class music must correspond to the needs of the working class “as a means of ideological propaganda and fight”. Relying on the historical musical forms of revolutionary movements, the most appropriate form of workers’ music is for Markovac a revolutionary song, whose words should express and represent “in a clear and convincing way the workers’ matter, show workers’ life and circumstances in the present and past, fight for rights and more, in the right light.” The music should be “virtuous, concise, militant, so that it will not stun, but will provoke in everyone the ultimate strength, effort, activity and enthusiasm”. He indicates that such music should be simple, written for one, two or three voices at most, with instrumental accompaniment if available. The simplicity of this music should be reflected not only in moving away from the intricacies of bourgeois art, but also in reflecting the material conditions and hard everyday life of the working class, since “a worker exhausted by daily work does not have enough strength in his free time to learn or to practice anything strenuous or harder to understand” and has ” no pre-education for intricate works of art”.

In such conditions, Markovac believes, choir singing proves to be the most effective form of working-class music. On the one hand, it enables the realization of the imperative of collective participation of workers because “singing in a choir is the most convenient means of creating a sense of community”, and is on the other hand not conditioned by special spaces or instruments – workers and their voices are all that’s necessary. For Markovac, collective participation does not only mean mere reception (e.g. visiting concerts), but also participation in the process of making music. Thus workers’ revolutionary songs shall not only be different in their content and form, but shall demand different performance conditions: “It is no longer music for concert halls, but for workers’ meetings, choirs, trips, etc. That’s music as a reflection of a community”.

To summarize, for Markovac, amateur music was extremely important in creating a new workers’ culture, but at the same time it served as a space for agitation and political education of workers. As an example of such work, we can use the workers’ mountaineering association “Friend of Nature”, which was closely related to the USSR. In 1934, Markovac took over the leadership of the mass choir and orchestra of mandolins and guitars. In accordance with his principles, revolutionary songs were increasingly being introduced into these ensembles. These compositions were simple, written for two to three voices with instrumental accompaniment, “of militant content and of mass atmosphere”.

Due to the abovementioned political repression and censorship in that period, public manifestations of this type were impossible, so the concerts most often took place at the so-called mountaineering meetings – mass mountaineering excursions in the vicinity of Zagreb, which gradually turned into political events led by communists. After the presentation of political papers, concerts of mass workers’ choirs and orchestras were held regularly.

With the establishment of the Workers’ Cultural and Educational Community, various cultural and educational societies come together under a single leadership. Various ensembles led by Pavle Markovac were connected and mass political and cultural-educational events were organized, in which an increasing number of workers participated. The first concert on May 28 in 1938 drew about 8,000 visitors while for one of the last concerts 12,000 tickets were sold. For Markovac, these events had “as well as every strike and every political manifestation a certain influence on the development of awareness and militant unity of workers”. At the very end of 1940, the Cvetković-Maček government made a decision to dissolve the URSS with the Workers’ Cultural and Educational Association. Shortly thereafter, Markovac was arrested and eventually killed in July of 1941.

*The text was first published at: http://slobodnifilozofski.com/2021/12/o-revolucionarnom-muziciranju-pavla-markovca.html, 24 January 2021